The CIPD Good Work Index is an annual benchmark of good work in the UK. Each year, the CIPD surveys thousands of workers to ask about the everyday realities of their own work and how it impacts their health and wellbeing. Its 2024 report is out now.

Workers who are underemployed fare poorly in the quality of their work. They work below their potential or preference in terms of wages, hours, and/or skills.

In this blog, we reflect on wage-underemployment: those workers who are underpaid for the work that they are doing, drawing on our research conducted as part of The Underemployment Project.

Good work

The ‘Good Work Index’ states that to be ‘good’, work must be ‘fairly rewarded’ and ‘give workers the means to securely make a living’.

The CIPD defines as ‘good’ work that:

- is fairly rewarded

- gives people the means to securely make a living

- provides opportunities to develop skills and a career and gives a sense of fulfilment

- delivers a supportive environment with constructive relationships

- allows for work–life balance

- is physically and mentally healthy for people

- gives people the voice and choice they need to shape their working lives

- is accessible to all

- is affected by a range of factors, including HR practices, the quality of people management and by workers themselves.

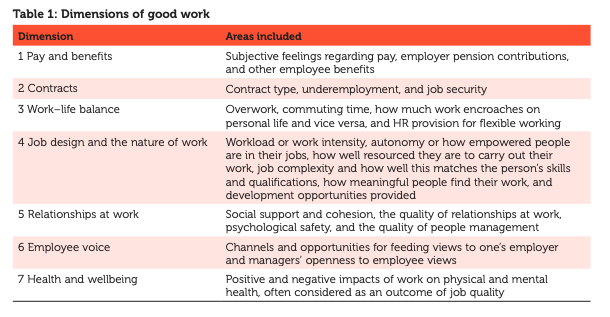

The index uses seven dimensions to classify work as good or bad:

(CIPD Good Work Index 2024, p. 3)

Pay and Benefits: Wage-underemployment is Bad Work

A wage is a crucial part of a job. According to the CIPD (2024, p 9), nearly 40% of the workers surveyed felt that a job is just about the money. While more than half (57%) felt that they would enjoy their job even if they did not need it for the cash, pay is still an important indicator of whether a job is good, bad or somewhere in between.

The CIPD also asked workers if they thought that they were paid appropriately for the responsibilities they had at work. The 2024 report finds ‘modest progress’ in the private sector but very little/no improvement for public sector workers.

The Underemployment Project is identifying how many and which workers are underpaid for the work that they are doing: the wage-underemployed. Wage-underemployment is a complicated notion, and we approach it in different ways.

We compare the wages of workers with others in their occupational grouping. Defining being underpaid as earning wages that are at least 20% lower than the median for their occupation, we show that wage-underemployment is prevalent in the UK, affecting almost a third of working women and over a fifth of working men, with levels persistent over time. Wage-underemployment impacts most heavily on younger workers, people working in accommodation and food service industries, and, perhaps surprisingly, managers and professionals.

We are also interviewing workers who self-identify as underemployed. Our findings reveal further complexities beyond the above objective indicator of wage-underemployment. While the pay rate itself is of crucial importance, other factors come into play. As the Good Work Index indicates, individuals also assess their pay in relation to other financial benefits at work (such as discounts), costs associated with work (such as transport and childcare costs), impact on social security payments, and whether they feel that their work is valued. Feeling valued is associated with fair renumeration for their work, as well as recognition by employers, managers, and customers.

Many of the participants in our project are doing challenging jobs whilst earning below the real living wage, providing essential services in healthcare, support work, hospitality and retail. One of our participants works in adult mental health services, earning £11.03 an hour and working 16-hours per week on a shift rota. She is experienced, has a range of qualifications, and is expected to carry out senior functions within the team. However, she is not eligible for promotion in her current workplace because senior positions are all full-time, and, due to caring responsibilities, she needs to remain part-time. She told us that her employers:

‘want to use my skills but they don’t want to pay me for them’

This subjective wage-underemployment: how workers assess their own jobs, is therefore as complicated a notion as objective measures that aim to quantify underemployment. To fully grasp subjective wage-underemployment, we need insights into workers’ lived experiences.

For more details on our research

Underemployment is widespread and growing in the UK, bringing significant economic and social consequences.

In the Underemployment Project we are tracking levels of underemployment over time to detail the composition of the underemployed workforce, pinpoint the predictors and outcomes of being underemployed and highlight the lived experiences of underemployed workers.

Our project team includes Professor Vanessa Beck (PI), Dr Levana Magnus and Carolyn Morris (University of Bristol); Dr Luis Torres, Mr Miguel Munoz and Professor Tracey Warren (the University of Nottingham); Dr Vanesa Fuertes (University of the West of Scotland); and Professor Daiga Kamerāde (University of Salford).

The research involves collaborative work with four partners: Bristol One City, Nottingham Citizens, Salford City Council, and the Poverty Alliance, Glasgow. Its advisors include the CIPD and the TUC.

What next?

For the next stage of our research, we are looking to speak to employers, employer federations, and trade unions, to learn how organisations manage resources and demands around hours, skills, and wages. As part of our conversations, we will explore what underemployment, or labour underutilisation, means to employers, and what the implications are regarding productivity, flexibility, recruitment and retention.

If you are interested in taking part, or would like more information, please contact:

Dr Levana Magnus, University of Bristol Levana.magnus@bristol.ac.uk, or 07824 162175.